Biology Of The Northern Prairie Skink, Eumerces septentrionalis (2001)

By Errol J. Bredin

Errol Bredin grew up on CFB Shilo, which occupies part of the Carberry Sandhills in Manitoba. He has been employed as a musician, writer, businessman and researcher, and his love for the Carberry Sandhills has unified it all. He follows in the foot steps of some famous early naturalists, the Criddles of Aweme and Ernest Thomson Seton, who earned their stripes in Manitoba's Carberry Sandhills region. Without going on to post-secondary studies, Errol built a professional network and a skills-base that has allowed him to be an excellent researcher and a strong voice for the preservation of the area.

Description

The Northern Prairie Skink is a smooth, shiny, alert lizard that, if seen, can prove very difficult to catch. Adults range in length from 127 mm to 204 mm (5 to 8 inches), with older ones not necessarily being the larger. With reptiles in general there appears to be extremes in retardation or acceleration of growth giving wide ranges in adult sizes.

The skink is a "many striped" lizard with a body pattern consisting of alternating stripes of light ashy olive, dark olive, and black lines. The belly can be a pale yellow, cream, or a faint bluish colour. Chin, throat, soles of the feet and sometimes a chest patch tend to be yellowish to pale yellow. The limbs are dark above and bluish-grey or yellowish underneath. A notable feature of young skinks is a brilliant blue tail, which dulls with age.

Classification

Here's the taxonomic classification of the northern prairie skink:

Kingdom: Animalia Phylum: Chordata Class: Reptilia Order: Squamata Suborder: Lacertilia (lizards) Family: Scincidae (the skinks) Genus: Eumeces Species: septentrionalis

Name Derivation

Scientific name: "Eumeces" is from the Greek prefix "eu" meaning true or good, and the Greek "mekos" meaning size or length. "Septentrionalis" is Latin for northern.

Common Name: The name, northern prairie skink is pretty logical in that this is a skink of the northern prairies of North America. Not so obvious is the origin of the word "skink". Anybody out there have a clue?

Distribution

The Northern Prairie Skink is Manitoba's only lizard and outside of some 177,000 hectares of CarberrySandhills habitat, it is found nowhere else in Canada. The skink migrated into Manitoba many thousands of years ago from the south. Today, the northern apex of the continuous range of this species reaches the extreme southeastern corner of North Dakota and central Minnesota, some 500 km south of the Manitoba population

There are two distinct subspecies of the prairie skink (Eumeces septentrionalis), the northern (E. s. septentrionalis), and the southern (E. s. obtusirostris), and their ranges are disjunct. Manitoba's skink is an isolated population of the northern prairie skink.

At its height, glacial Lake Agassiz covered much of Manitoba and tapered south into North Dakota and Minnesota terminating in the vicinity of the extreme southeastern corner of North Dakota. As this immense lake receded and the climate moderated it is believed that the skink moved northward following the exposed beach lines of Lake Agassiz. It appears that this movement followed both east and west shorelines. Adjunct or isolated populations of skinks are found in two areas of northwestern Minnesota, the Agassiz Dunes Natural Area just southwest of Fertile, and farther north in a small tract of sandy dunes near Lake Bronson. Along the remnant western shoreline of Lake Agassiz there is an isolated occurrence of skinks just west of Fargo, North Dakota and some 300 km to the northeast, far removed from its relatives, the Northern Prairie Skink has found a home in the Carberry Sandhills. As climatic conditions changed, harsh winters soon eliminated skinks living on heavier soils where they could not burrow below frost lines. The ancient Assiniboine Delta provided these small nomads with a sandy security and today the Northern Prairie Skink is a truly unique member of Manitoba's reptile fauna.

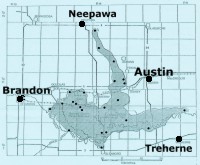

The distribution of the Northern Prairie Skink in Manitoba is centered throughout Sprucewoods Provincial Park and the CFB Shilo military training range. From this central core, its distribution extends in a narrow finger between Carberry and Sidney to a point just south of Neepawa. Another narrow strip of suitable habitat runs eastward with skinks being sighted 15km north of Treherne. Diminished numbers of skinks extend south to the Glenboro area. The primary factor in the distribution of the skink is soil type. They occur almost exclusively on what is termed Stockton Loamy Sands, these are the sands that comprise the Assiniboine Delta.

Skink range in Manitoba (Nature North).

Life Cycle

With the advent of spring, and soon after the lavender tinge of blooming Prairie Crocus has left the ridges, skinks begin to emerge from hibernation. Weather plays a definite roll, and dates vary from year to year, but emergence usually takes place in late April to early May. This year (1999) is the earliest I have sighted active skinks, the date was April 22nd. Indications are that males tend to emerge first, and soon after their jaws and throat begin to turn a distinctive, bright orange. When this temporary coloration is at its height the breeding season begins, and it continues from mid-May to early June.

Skinks will breed in captivity, as I found by placing pairs in a terrarium that had been prepared to be as close to their natural surroundings as possible. When the male begins to show interest in the female he arches his tail upward with the tip dragging on the ground. He will then begin to pursue the female, nudging her gently and lightly biting her torso. This continues for ten to fifteen minutes. Finally, he grasps the skin above her front legs firmly in his jaws, encircles her and copulation occurs, lasting a minute or two.

The breeding season affords the best opportunity to observe skinks, as this is when they are most active. As the breeding season ends, both males and females tend to become extremely secretive, with both sexes spending greater amounts of time under some form of surface cover. Males quickly lose their distinctive orange coloration around the jaws, and determining the sex of a skink becomes very difficult.

After a gestation period of around forty days the female lays an average of eight eggs in a small nest cavity. These nests, as a rule, are under a piece of surface cover such as a log, piece of board, sheet of tin, etc. One nest I uncovered was under a discarded barrel lid with the eggs buried at a depth of 10 cm. in loose soil. The eggs look like extremely tiny chicken eggs, and when first laid are bright white and average 7 mm in width and 12 mm in length. The eggs have a thin, elastic, parchment-like shell that is easily punctured. During the incubation period the eggs absorb moisture and swell up considerably.

The female skink broods her clutch of eggs. After breeding a female in captivity I decided to keep her during gestation and egg laying as well as brooding, with the hope I might observe a successful hatch. Soon after gestation had begun she prepared a small nest cavity under a piece of board. Forty-one days after being last bred she laid a clutch of six eggs. Most of her time was then spent with the eggs, she rarely came out to bask in the sunshine (a favorite activity) or to feed. When the board was raised she could be observed lying with her body coiled around the eggs. If the eggs were moved outside the nest she would immediately begin replacing them by rolling or pushing them with her nose or a loop of her tail. Several times I observed her moving the eggs about in the nest cavity herself. Studies have shown that female skinks seem to sense subtle changes in humidity levels and will move their eggs in response to those changes. Thirty-six days after being laid a single egg hatched and the young skink and its mother were returned to the place where I had captured the female.

As soon as the eggs begin to hatch in the wild, or shortly after, the female will leave the nest. Within a few days the young begin to disperse from the nest and forage for food. Hatchlings are very dark upon emergence from the egg and average around 58 mm to 62 mm in length. They are highly active. I've often observed them darting around with their bright blue tails arched aloft. The earliest date I've found hatchlings in the wild is August 4th . One hatchling, last sighted on September 9th, when measured, revealed a growth rate approaching 1 mm per day. These young skinks reach sexual maturity after emergence from their second hibernation.

Habitat and Home Range

Skinks tend to "colonize" around an area supplying some form of surface cover. If one is sighted chances are good there's more in the immediate area. The size of a colony depends on the amount of surface cover available. In a purely natural setting this cover is usually a piece of fallen tree, and the colony quite small, three or four adults. In other instances, small concentrations of skinks have been observed inhabiting small excavations under a thin layer of topsoil. I have found individuals in shallow burrows under a piece of bark or a decaying tree branch.

It seems that humans have an inherent ability to "litter" the landscape. This highly questionable practice has actually aided Manitoba skinks along with some of our other reptile species. Skinks are quickly drawn to junk scattered about on the surface. If this refuse happens to be flat boards, bits of sheet tin, even cardboard, then skinks are sure to set up housekeeping immediately upon finding it. They seem to prefer man-made surface cover. Some of the largest concentrations of skinks I have found are in litter piles and places where old buildings have been torn down, with boards and roofing tin left lying about. In one instance I routinely checked a single piece of tin 1 m square over a period of four summers and captured, marked, and released 16 skinks that were sheltered under it.

Skinks, once settled, tend to stay in close proximity to their chosen cover and spend a substantial amount of time under it, lying quietly in small excavations. Over a period of three months I regularly checked a plank 3 m long by .25 m wide. This plank was home to four skinks that I marked for easy identification. Not once did I see one of these skinks out on the surface, but each time I lifted the plank I recaptured all four individuals. There was other suitable cover a meter away, but it was seldom, if ever, used. They do forage for food, but the evidence indicates that they don't venture very far away from their protective cover. In many instances food likely comes to them, in the form of crickets seeking shelter.

During the summer of 1981, I monitored eight colonies of skinks on the CFB Shilo ranges. Individuals were captured, measured, marked, and released. One of the reasons skinks were marked was that, when recaptured, data could be compared and movements determined. In all but two instances there was no noticeable movement, with recaptures occurring within 1.5 m of the point of original capture. However, some individuals do move and can cover considerable distances. As with some humankind, certain skinks succumb to "wanderlust" and set off in search of adventure. Others are forced to leave familiar surroundings when the structure of a colony changes. Perhaps an old male is set upon by a young successor. Territorial fighting is common during the breeding season with the loser forced to relocate. Hatchlings are very active and before reaching sexual maturity seem to travel about in search of a permanent home. Forced relocation can also occur. I noted one instance when, during the winter, an area of scattered litter was cleaned up by military personnel. When skinks emerged from hibernation in the spring they found their familiar cover gone and were forced to move. Late that summer I located one member of this abandoned colony under a piece of plywood 156 m away from the cleaned-up site.

Food

Skinks have a preferred diet, and it includes crickets, grasshoppers, and spiders. Other insects and insect larvae are second choice foods. Ants, a readily available food source, are for the most part abhorred. Cannibalism does occur, with adult skinks preying on their own young.Protective Adaptation

The Northern Prairie Skink has an interesting protective adaptation. When pursued by a predator, the skink will arch its long tail and vibrate it vigorously. The attacking animal pounces on this "decoy" and the tail is quickly dropped off, while the skink scurries for cover. This is one reason care must be taken in the handling of skinks, for the tail is easily lost. I have often observed that the tail can be whipped off without being forcefully grabbed. It is amazing to watch as the tail literally leaps and bounds while vibrating vigorously. This nerve action can last ten to fifteen minutes, ample time for the skink to escape while the predator is thoroughly distracted. After losing a tail, the exposed flesh soon heals over and a new tail begins to grow again. A regenerated tail is more complete in young skinks. When an old adult loses a tail the resulting growth is usually quite short and sharply tapered.

Because of their secretive nature and lightning-like speed when disturbed, I don't think any great numbers of skinks are lost annually to predation. However, studies indicate that natural predators include the Western Hognose Snake, hawks, owls, raccoons, skunks, mice, and shrews. Mice appear to be the most serious threat as adult skinks often are found with scaring indicative of attacks by a small mammal. I often find Deer Mice resting under a piece of cover where I've sighted skinks. At times they force the skinks out, or perhaps they kill them outright.

Final Thoughts

Standing high atop a ridge, I have been fortunate enough to witness another sunrise deep within the heart of the Carberry Sandhills. The thick mists have risen and evaporated from over the tamarack bog as I turn and head down the steep slope to the undulating mixed-grass prairie. There's work to do. I currently have 20 reptile-monitoring sites on the CFB Shilo ranges and my little, lifelong friends await my visits.

People ask me: "Why this interest in skinks?" Granted, they seem to have neither a harmful or beneficial effect on overall human affairs or economy. Nevertheless, there may be various unsuspected relationships, and I cannot forget a passage read some time ago: "Everything that lives has something of value to share with you - whenever you are ready for the experience."

For More on Skinks

Here are some other resources with information on Manitoba's lone lizard.

Books/Reports

- Bredin, E.J. 1989. Status report on the Northern Prairie Skink (Eumeces septentrionalis) in Canada. COSEWIC status report. Unpubl. Ms. 39 pp.

- Conant, R. and J. T. Collins. 1998. A Field Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians, Eastern / Central North America. A Peterson Field Guide. Houghton Mifflin Co. Pub.

Web Sites

- Biodiversity Database, Conservation Data Centre, Manitoba Natural Resources. Look in the "Field Guide" section for information on the status of this species in Manitoba.

- More reptile articles in NNZ: Garter Snakes & Garter Snakes in the Class Room

Bredin, Errol J. "Biology of the Northern Prairie Skink, Eumeces septentrionalis". Previously published by NatureNorth.Com (www.naturenorth.com) Summer edition, 2001.